Prior to the introduction of environmental banking as a solution for permitted impacts, there was so little transparency that few people outside the industry realized the magnitude of project failures. In a study by the National Academy of Sciences in 2001, it was revealed that only about half of the required mitigation had been constructed and that compliance inspections were rarely done. Projects that had been completed often did not offset the permitted impacts. Severe regulatory staff shortages were common. Thousands of impacts were permitted each year that were never offset with equivalent restoration. Actual replacement values were estimated as low as 20%. (Sciences, 2001). Tens of thousands of acres of wetlands continued to be destroyed annually. A joint study by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service, which covered 2004-2009, revealed an estimated “net loss of freshwater vegetated wetland area of 328,800 acres.” (Dahl 2013)

Since failure was so common in these forms of mitigation, many felt that banking wouldn’t be any better. It was considered a last-ditch effort after everything else had failed. The results over time proved otherwise.

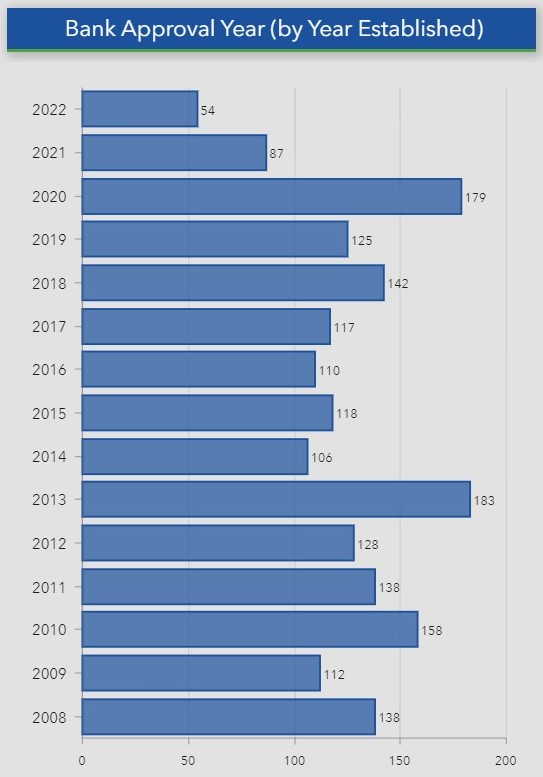

( * 2022 data may be incomplete)

Environmental banking has demonstrated itself to be the most successful program in history for restoring and protecting the environment. It is extremely rare for a bank to fail. Its continued expansion presents the very real potential to reverse the continued march of environmental destruction. According to Palmer Hough and Rachel Harrington of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in their recent retrospective on the program: “One of the most notable trends over the past 10 years.

To Read More about the Values of Environmental Banking: